What is

Optic Nerve

Hypoplasia

ONH & The Eye

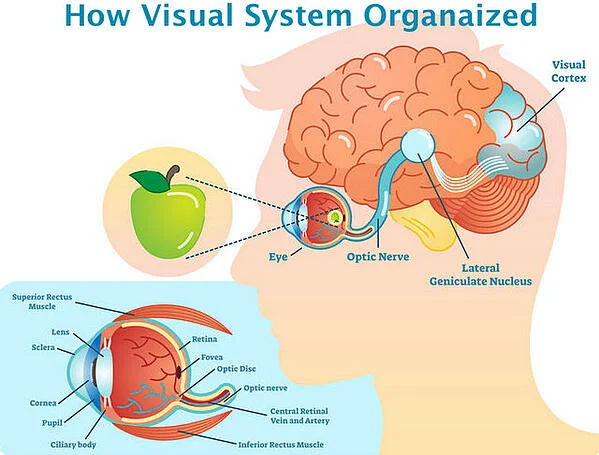

ONH stands for optic nerve hypoplasia and is a condition in which the optic nerves do not fully develop. The optic nerves travel from the back of the eye to the brain and transmits the visual signals to the section of the brain that transforms them into images (AAPOS.org). Because of the underdevelopment of the nerves during the first trimester of pregnancy (AAPOS.org), the nerves do not transmit these signals as well (AAPOS.org).

The condition is present at birth, but doctors and researchers have not been able to find a clear cause (AAPOS.org). ONH is considered a stable, non-progressive condition. This means that the condition will not get worse over time (AAPOS.org). As a child moves through their second and third years, there may be a slight improvement as the visual pathway matures (NCBI). It is the third most common cause of visual deficiencies in children (esighteyewear.com).

Optic nerve hypoplasia was once thought to be a rare condition however, its prevalence is on the rise and occurs randomly (esighteyewear.com). There are a few theories as to what causes the condition, but nothing has been able to be proven to date.

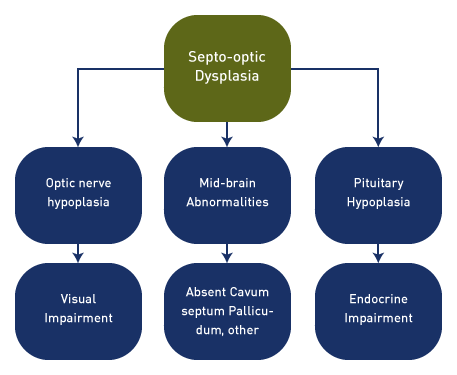

This condition can also be known as DeMorsier’s syndrome and septo-optic dysplasia (SOD) (allaboutvision.com). It is marked by a number of signs and symptoms affecting both vision and behavior. Children can exhibit any number or combination of the following (esighteyewear.com):

- Lack of visual detail & general blurring

- Lack of peripheral vision

- Light perception can range from normal to none

- Lack of depth perception

- Photophobia (sensitivity to light)

- Muscular and mental delays

- Squinting, lowering of the head and avoiding light

- Limited food preferences

- Using alternative methods of stimulation

How ONH Affects the Eye & Vision

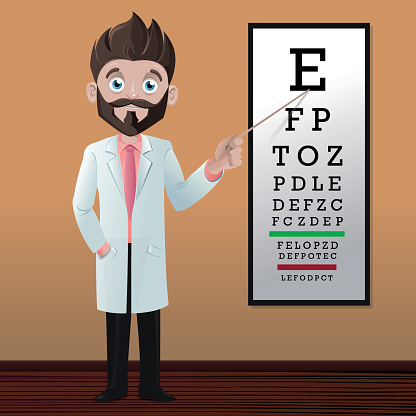

Optic nerve hypoplasia causes visual impairment and blindness in 15%-25% of children (esighteyewear.com) but does not normally present with major physical deformities. It is impossible to determine the visual acuity of an ONH patient just by the appearance of the optic nerve. A visual acuity test may be performed to help determine how much vision a patient has. This type of test is performed using the Snellen Chart, which is a standardized chart that can be on a card or on a screen. The chart is placed 20 feet away and each eye is tested while the opposite is covered to determine the smallest letters the patient can read (MountSinai.org).

The results are listed as a fraction where 20/20 is considered normal vision. The top number is the distance between the patient and the chart, and the bottom number is the distance between the chart and a person who has normal vision. So, in this instance, the patient with 20/20 vision, has normal vision. A patient that has 20/30 vision can read the letters at 20 feet that a person with normal vision can read at 30 feet (MountSanai.org).

Some ONH patients have enough vision to read these Snellen charts while others do not. The vision of a patient can range from mild (20/20 vision) to severe (total blindness) in one or both eyes (AAPOS.org).

Two other secondary conditions that are common with ONH are known as nystagmus and strabismus. Nystagmus is the involuntary rhythmic shaking of the eyes (allaboutvision.com). This shaking can be side-to-side, up and down, or in a circular motion which makes it difficult to focus on objects. Strabismus, also known as “crossed eyes,” is a misalignment of the eyes which causes one eye to move inward or outward while the other remains focused. This prevents both eyes from working together properly (allaboutvision.com). These conditions are both common in patients with ONH because they already have a decrease in their vision. This decrease in the vision inhibits their ability to focus and train the muscles of the eye to maintain proper alignment.

Associated Disorders/Conditions & Risk Factors

Optic nerve hypoplasia rarely presents by itself. It often occurs with other functional and physical abnormalities (esighteyewear.com) that can include:

- Autism

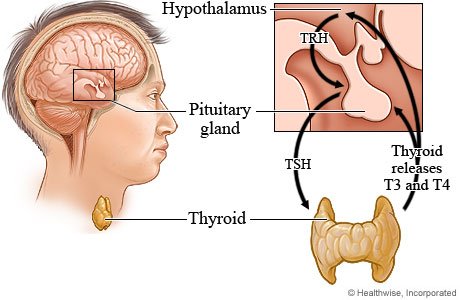

- Midline anomalies in the brain such as cerebral atrophy & septo-optic dysplasia (is the combination of optic nerve hypoplasia, an under active pituitary, and abnormal development of structures in the middle of the brain)

- Hormonal imbalances

- Diabetes insipidus (body makes too much urine)

- Hypothyroidism (under-active thyroid)

- Hypoglycemia (blood sugar level, glucose, is lower than the standard)

- Cerebral palsy (affects a person’s ability to move and maintain balance)

- Seizures

- Pituitary gland that functions abnormally

The conditions listed above do not all appear in every patient. They can appear in any number or combination as well as result in mild to severe disability (esighteyewear.com) and developmental delays (AAPOS.org).

Hormonal deficiency occurs in the majority of ONH patients and 15% have significant hormonal deficiencies (AAPOS.org). The severity of hormonal deficiencies varies from patient to patient but most often affect the pituitary gland, thyroid gland, or both. These hormones have a significant role in regulating blood sugar, growth, metabolism, and other important bodily functions (allaboutvision.com).

Developmental delays and intelligence also range from normal to severe and the patient and family often need a team of doctors and therapists.

Diagnosis & Treatment Teams

Diagnosis of ONH is often made during a dilated eye exam (AAPOS.org) but other tests, such as an MRI and bloodwork to test hormone levels (endocrine), may, and should be performed, to verify (AAPOS.org). Once an ONH diagnosis is made and tests for other secondary conditions are completed, a team of doctors and therapists can be assembled. This team can consist of any combination of the following depending on the needs of the patient:

- Pediatrician

- Ophthalmologist/low-vision optometrist

- Neurologist

- Endocrinologist

- Physical therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Speech therapist

Treatment & Management

The first thing to realize when it comes to treatment of ONH is that there is no cure, at least not yet. Please refer to our news and updates page where we will post information about advancements and studies being conducted around the world.

The second thing to realize is that early detection, a support system, and observations are important to minimize the impacts caused by ONH and any other secondary conditions (esighteyewear.com).

As far as treatments go, there are a few international companies providing stem cell treatments to improve a patient’s visual acuity and maybe physical functioning of the body. Many studies claim this treatment does not work, but many patients and families report improvement after these treatments. This type of treatment is for each individual family and patient to decide if it is worth the try. For more information about this type of treatment, Giving the Gift of Sight recommends visiting the Beike Biotechnology’s website here (Beike).

Management of ONH and related conditions really comes down to learning everything you can (whether you are the patient or the care giver) about each diagnosis and collaborating closely with the doctors and support team.

Hormonal deficiencies, seizures, and other conditions may be treated with medication to regulate or control the symptoms. Regular doctor visits are necessary to determine if medication levels are correct, the patient is developing as expected, and to stay ahead of any other challenges that may present themselves.

Our Experience & Tips

Our organization was formed because a child close to us, Heather, was also diagnosed with ONH and other related conditions. From our experience, we also recommend the following management tips.

Observe yourself (if you are the patient) or your child (if you are the care giver) and keep records of everything.

Example

We set up a binder that included all the essential information regarding Heather that a hospital or emergency room might need. In this binder we had a list of the diagnoses and medications, a list of the patient’s doctors and therapists, an observation tracking sheet, doctor visit summaries, and pages where the patient or care giver can take notes during appointments or hospitalizations. This came in very handy during emergencies when Heather was taken to the emergency room. We were able to hand the binder over, point out the tracking sheet if Heather had been sick for a while, which listed any over-the-counter medications given, her temperature readings and behavior during that period. Once the binder was in the hands of the emergency staff, we, as care givers, could answer the more important questions from the doctors while the nurses updated the chart.

Get a full work-up at the beginning and especially when you suspect anything is wrong. A full work-up in the beginning can help identify any other conditions that may not be obvious but could be contributing to any current problems. Another example of when you should insist on a full work-up is if you believe something is wrong. You, as the patient or care giver, know better than anybody else because you live with it every day. You may see small signs that something is wrong before the big one.

Example

We saw Heather develop a slight tick in her fingers. We called her pediatrician and scheduled blood work to check medication levels as this tick is something she did during a seizure. Before the bloodwork could be completed, she had a full-blown seizure (and there are various kinds, so care givers should also be knowledgeable about which ones are common for the patient). Once in the emergency room, the blood work showed that her seizure medication levels were too low because she had grown, and they were adjusted.

Be your or your child’s advocate. If you believe something is wrong, speak up. Do not let a doctor just tell you everything is okay. Make them explain why they think that or explain test results. You need to be satisfied with their answer. And if anything does not make sense, ask for a second opinion.

Example

After 15 years of learning, our observations and research of Heather’s diagnoses came in handy. This example involves an emergency room that was not familiar with Heather. She had been diagnosed with the flu the day before and there is a certain point when we are caring for her that we knew we could not give her what she needed fast enough (fluids and glucose to raise her blood sugar), so we took her to the emergency room to get those. Upon arrival, the doctor examined her and agreed with us about what she needed, fluids and glucose, and they also did the routine bloodwork and flu test. Two hours later, a different doctor came in, did not examine Heather, and started diagnosing her with diabetes based on the bloodwork and wanted to administer all sorts of diabetic medications. These medications would have killed her. The doctor did not read the rest of her chart, just the test results. We then signed her out against medical advice. Please note that we do not recommend this action, but we felt in this situation it was called for because the doctor would not listen to us and do his due diligence when taking over a patient from another doctor. Do not ever let a doctor dictate to you. They should be working WITH you.

Look for a functional optometrist. This is not necessary, but it can help. A functional optometrist can perform some basic tests and they are trained to interpret the results and behavior of the patient to determine what kind of visual acuity they have.

Example

In Heather’s case, we learned what colors she can identify, that she has more peripheral vision than she does central, and she is far sighted. Now she cannot see far, far away, but she can focus better if the object is 8-12 inches away from her eyes, versus 4-6 inches. This helped her team of therapists determine better ways of working with her.

Have an emergency plan. We spent a lot of time in and out of emergency rooms the first few years after she was diagnosed. Each time we learned something new and as we learned, it got easier.

Example

We developed an emergency plan, which was written down and important information included. This plan was given to each person she spent a significant amount of time with, a copy is also in her medication case, copies went to each of her teachers, therapists, and school nurse. Everybody was trained in the administration of emergency medication and in what order procedures should be followed. The family also keeps a “go bag” or “bug out bag” (a bag packed with essentials like a change of clothes for patient and care giver, toothbrush, shower essentials, and the basics) in the vehicle in case an emergency hospitalization occurs.

Have an emergency savings fund. This emergency fund will help alleviate the financial stress of hospital stays because it requires gas and food for care givers to be with the patient when they need it most. You can find more information about this at (Dave Ramsey).

Tackle boxes make GREAT medication organizers! We got ours from Dick’s Sporting Goods and it has held up for 10 years now. We really like the one pictured to the right, but it’s a good idea to take your medication bottles with you and test the fit and customization capabilities.

Lastly, be flexible, patient, and creative. Each patient is different. And it can get frustrating for both the patient and the care givers. We must remain flexible and adjust as things change. We must also stay creative, especially with coping tactics. Many ONH patients have certain things that bother them more than a normal person and it can put them into an episode of crying, screaming, or even silence. So different ways to manage these situations may need to be developed.

Example

For us, when Heather would get frustrated and scream and cry, we found that music and massage with pressure helped calm her down. It distracted her from the problem and gave her both auditory (hearing) and sensory (touch) stimulation. Just a quick side note, many patients with ONH also look for other types of stimulation because they do not get the visual stimulation from the eye. This can include rubbing their hands, feet, or head on different surfaces (Heather developed a bald spot on her head for a little), swinging, roller coasters, massage with pressure, music with strong beats, vibrations from toys, lights (if they have some visual acuity), wind, water, etc. You just have to find what works.

So, in summary, the best defense is observation and knowing how the patient responds to different circumstances, and this may take time, even years, to learn. So do not despair and do not think you are a bad parent if this happens. Just keep notes for the future, develop strong relationships with your doctors, therapists, and teachers, and as you or your child grows and learns to communicate better, the chaos will turn into routine.

Also remember that you are not alone. A strong community has been built here (FB Support Group).

We do plan to start a blog to share some of the tips and ideas that have worked for us and others over the years so check back often!